What if they’re right? What if a nuke drops, or climate change turns the world into a foaming puddle, or the next pandemic is spread through selfies? Billionaires have recently been spending millions building themselves customized bunkers, in the hope that they can ride out the apocalypse in splendor. In January, a video surfaced of the rapper Rick Ross bragging that his bunker will be better than Elon Musk’s bunker. (Musk is not known to have a bunker, but that’s a detail.) Ross’s bunker will have multiple “wings” and a “water maker.” Also, plenty of canned goods. Ross’s bunker might even have its own bunker. But what about me—and, if I’m being generous, you? Are there affordable underground shelters available for us to hole up in?

A few months back, I started to scan real-estate Web sites. Hmm, I wondered. Might throw pillows brighten up the underground scheelite mine in Beaver County, Utah, that was converted into a community fallout shelter during the Cold War (a steal at nine hundred and ninety-five thousand dollars, when you consider how many light-bulb filaments you could make from the leftover tungsten you could knock loose)? Or how about the concrete-and-steel stronghold in Hilliard, Ohio, built by A.T. & T. and the Army in 1971 to protect the nation’s communications system in case of nuclear attack? It comes with a “1970’s-era smoking room.” (Note to self: Take up smoking a few months before world ends.) Would house guests get the hint if I mentioned that my new home had three-thousand-pound blast-proof doors? ($1.25 million for nine acres.)

I considered breaking the bank ($4.9 million) for a compound in Battle Creek, Michigan: more than two hundred and ninety acres encompassing several dwellings, the largest being a fourteen-thousand-square-foot affair that looks like a soap opera’s idea of a mansion, with indoor pool and “high-end” appliances (if there’s a Miele waffle-maker, I need that house!)—and, below, a spacious bunker with its own shooting range and grow room. (Phew! Who can survive without daily fresh fenugreek?) Unfortunately, the owner of that particular McBunker wouldn’t allow me to tour the place, because I couldn’t show proof of funding. This is a standard requirement when shopping for bunkers; so few “comps” exist that banks cannot assess their value, and thus won’t give mortgages.

After weeks of scrolling, I found a handful of dream hideaways on the market whose sellers were willing to let me take a tour. There were two bunkers in Montana, one of which sleeps at least ninety; a prepper bunker in Missouri that features an inconspicuous entrance and a conspicuous arsenal of guns (not included in sale, but makes you think twice before criticizing the kitchen-countertop choice); a defunct missile-silo site in North Dakota; and a twenty-thousand-square-foot cave in Arkansas used by its previous owner to raise earthworms. (Favorite bit of real-estate marketing copy: “The worm room speaks for itself.”)

I decided to tour the larger of the two advertised earth homes in Montana. Theresa Lunn, a local real-estate broker who specializes in bunker sales, showed me around. From the outside, this hole in the ground looked as if it could be the home of a paranoid hobbit. Built into an otherwise unremarkable snow-speckled knoll is a three-foot-thick concrete slab, artfully flanked by boulders. Positioned in the slab was a rusty steel door so tiny that I would have to duck to enter. Lunn took out a small key and struggled for a long while to open a padlock that secured a heavy chain around the door handles.

We were at the end of a long dirt road in the middle of Paradise Valley, not far from Yellowstone Park, but exactly where, I cannot reveal. I promised Lunn, who’d promised the seller, that the location would remain secret.

She had told me earlier that this was the largest of four getaways originally built in 1989 by a member of the Church Universal and Triumphant, a cult led by Elizabeth Clare Prophet, who predicted that nuclear Armageddon would occur in the spring of 1990, and urged her thousands of followers to bunker down ASAP. (She’d previously sent out a “save the date’’ claiming that the world would end the previous October, but she changed her mind.)

After Lunn got the door open, she ushered me into what looked like a large drainage pipe with ten feet of headroom, painted in a cheery shade of teal. This was the bunker’s entry hall. I made a mental note that, if I were to move in, I’d relocate the cartons of apple juice, canning jars, and other jumbled supplies piled there to the food pantry in the basement. Better yet, I’d toss them. I noticed that a bunch of the stuff was expired. Among the stored food: a three-foot-tall barrel of walnuts and cartons of barley, adzuki beans, “health food” mayonnaise, “home storage” wheat, and abundant bacon bits.

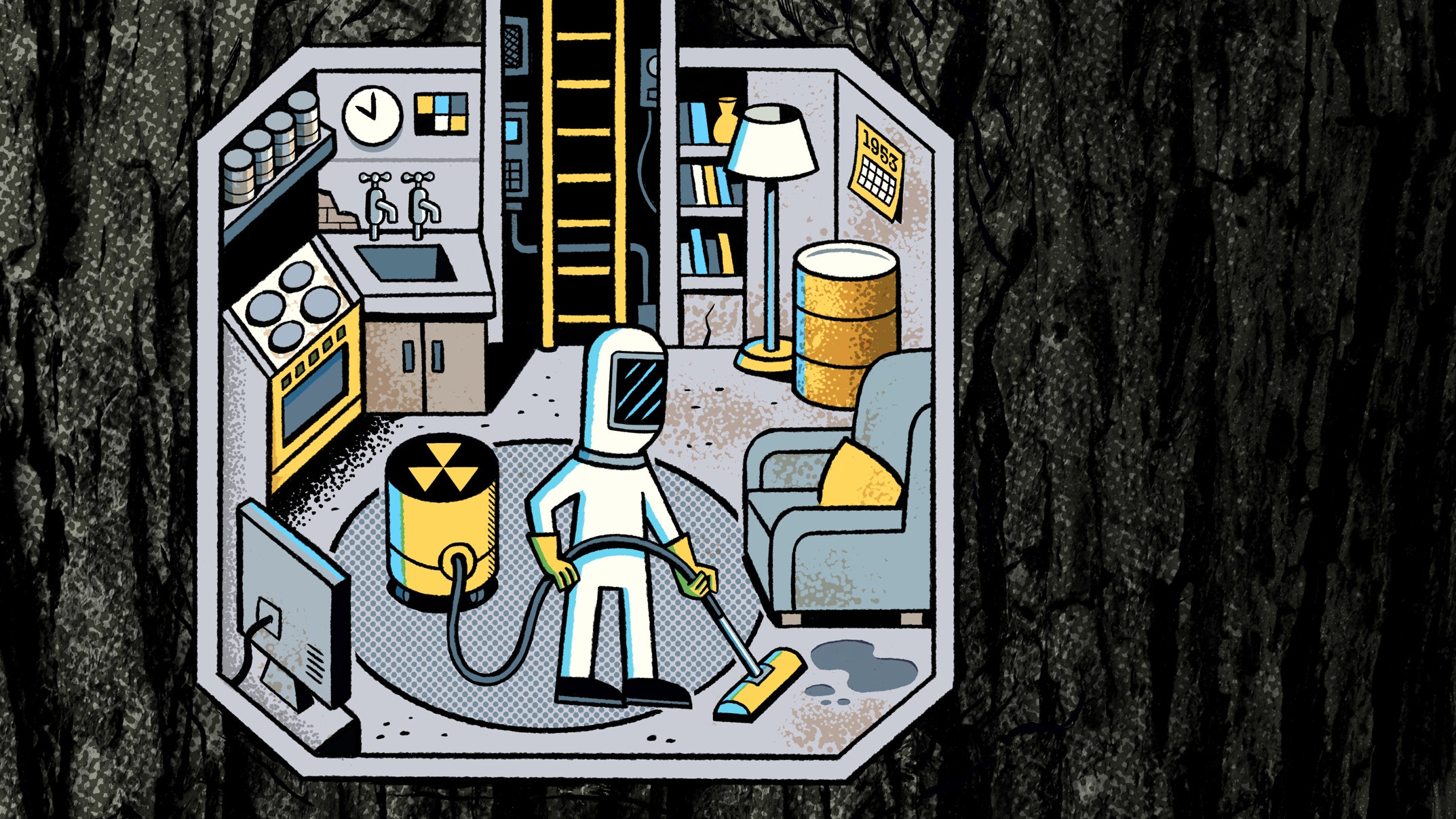

Just past the entryway, there is, for your convenience after a long day out in the radiation, a roomy decontamination shower alongside handy instructional posters. For example, “Eyes: Irrigate with large amounts of normal saline or water. Direct flow from inner angle (close to nose) toward outer angle of eye. Save fluid and survey. . . . If okay, wrap [self] in blanket and proceed to your room.” “Your room” would likely be a nook the size of a substantial walk-in closet containing four wooden bunks; some of the beds I saw were painted a Laura Ashley-adjacent shade of lilac (which coördinated with the chintz floral coverlets but not with the brown industrial carpeting or the blobby blown-insulation walls). If you are lucky enough to get the master bedroom, you’ll find a good amount of space and privacy, as well as a life-size marble-composite statue of the Virgin Mary watching over you. On a side table, I spied a souvenir copy of USA Today from September 12, 2001, with the headline “ACT OF WAR.”

“What I think is the most inadequate thing about the bunker is the laundry facility,” Lunn said. “When everybody’s out working in the fields or whatever, growing their own stuff, and then comes home. . . .” She raised an eyebrow. On a more positive note, she pointed out that the temperature never drops much below forty-eight degrees: “The cool thing is that the pipes never freeze!” When I asked her whom she viewed as her ideal buyer, she said, “It takes a special type. But at this price point, you couldn’t even pour the concrete used here.”

On the drive back to my hotel, I asked Lunn, partly as a joke, where the weapons were kept. “You weren’t shown them,” she said, dryly, then explained one of the regular gambits of the bunker-selling trade: “It’s very common to put in the listing that there are hidden doors and bookcases and rooms that will be shown to the buyer only once the property is purchased.” As we drove through picturesque mountain scenery, Lunn said that eighty per cent of the houses we were passing had bunkers underneath. There isn’t much bunker inventory these days, however, because owners don’t want to sell.

What was the most pressing fear, I asked. “You can just feel the general uneasiness,” she answered, and explained that a lot of her clients are “in the know”—meaning former C.I.A. or F.B.I. agents, ex-military, or ex-police. She asked, “Do you know why they all want property above twenty-five hundred feet?” Hint: It’s not for the views. An ex-NASA guy had told her that soon the water will rise, “and climate change has nothing to do with it.” Rather, it’s because “two or three planets or asteroids are going to collide and mess up the natural spinning of the Earth.”

I asked to what extent current events affect the bunker market. “Business improved after the Baltimore bridge collapsed,” she said. “Nothing like a big old boat taking out a bridge.” (Lunn has heard that the Russians or the Chinese were behind it, but let’s not get into that.) Among the eight or nine buyers who’ve come to tour the bunker I saw, she said that most were looking for a solid investment and protection against “an N.B.C. event”—nuclear, biological, or chemical devastation. “Or civil unrest, if there’s another biological attack on the country—as there has been once,” she said with a grim smile, referring to COVID-19.

The address of the bunker that Lunn showed me that day was listed as “123 Discreet Location, Montana.” I realized that selling something whose selling point is that nobody knows where it is presents a marketing challenge. Before heading out on my bunker tour, I had asked one broker about visiting Vivos Indiana, a multilevel underground complex “strategically located in Midwestern America,” according to its Web site. It’s operated on a “country club ownership model”; vacancies go for thirty-five thousand dollars per person. I was told that, as a reporter, if I were to visit, I would be picked up at the nearest town, Terre Haute, and, after I surrendered my phone, would be either put in a van with blacked-out windows, or be blindfolded several miles from the listing. I declined, thereby missing out on seeing what the Vivos Web site describes as an “impervious” complex that was built during the Cold War. Boasting twelve-foot ceilings, a checkerboard backsplash in the kitchen, plenty of board games, and leather sofas that look as if they came from Restoration Hardware, the place is guaranteed to withstand a twenty-megaton blast. And they’re concerned about intruders?

According to a 2023 YouGov poll of a thousand respondents, sixty-six per cent are worried that the human race will be wiped out by nuclear weapons; roughly the same number worry that we will be killed off by a world war; fifty-three per cent think the next pandemic could do us in; fifty-two per cent bet on climate change; forty-six per cent on A.I.; forty-two per cent on an act of God; thirty-seven per cent on an asteroid; thirty-one per cent global inability to have children; twenty-five per cent an alien invasion. Only a small chunk of people believe the end will come in the next ten years. But for the eight per cent who believe it’s “very likely,” that’s soon enough to make their starter home their finisher home, too. In 2022, the Pew Research Center found that thirty-nine per cent of adults in the United States believe we are living in end times.

These are the directions a visitor is given for how to reach the bunker listed above. On the outskirts of Mountain Grove (a town motto: “Take a closer look”) is a country road. Take that, and after you pass a lot of farmland and occasional fields of grazing cattle, you’ll come to a sign.

Wouldn’t a few potted petunias be a better way to enhance curb appeal? But now you’re on the premises; if still alive, read on. If an intruder: the barnlike galvanized-steel structure in front of you is a decoy; it contains twelve hundred and fifty square feet of nothing. The real house is underneath, and is breachable only via a set of stairs that is revealed when a diversionary staircase is retracted, using a remote control.

This bunker is for sale by owner, and the owner is Malachi Twigg, an Orthodox Jew who wears a yarmulke on his head and a Glock 17 on his hip. While Twigg showed me around, he explained that he built his retreat after moving from Chicago twelve years ago, as a precaution against tornadoes and invasions. Except for the lack of windows—“Nope, never miss them. You want to look outside, go outside,” he told me—the space feels like a regular apartment, with nice-sized rooms branching off a central hallway. Amenities include cedar-lined closets, taupe wall-to-wall carpeting, and an in-unit washer and dryer. Mounted in a wooden case, where others might have displayed their Hummel figurines, was a pair of assault rifles.

I asked Twigg how old he was. “Fifty-four? Oh, fifty-six,” he said. “What’s the point in counting during end times?” He explained that Biblical math, which is evidently very precise, suggests that—to make a long Armageddon short—“a bunch of countries” are going to gang up against Israel within six years; the Messiah will “get personally involved” and “wipe out two-thirds of the world’s population.” But, wait, there’s a feel-good ending: “All bad people will be gone.” Specifically, he added, in two hundred and sixteen years.

Most definitions of a bunker stipulate that the shelter be underground and used as protection from attack (or storms). In other words, dirt plus danger. Although the word comes from a Scottish term for “bench” which first appeared in the eighteenth century, bunkers have been around a lot longer than that. Consider, for instance, the sprawling subterranean cities of Cappadocia, in present-day Turkey. The cities’ groundwork was laid in ancient times, but they served as hideouts from the Muslim Arabs during the Arab-Byzantine Wars, starting in the seventh century A.D., and they continued to be used for centuries, affording refuge from the baddie du jour. Bunkers (and their cousins, trenches) were used extensively in Europe during both World Wars as cover against enemy fire, storage for weapons, and command centers. It was the Cold War, though, that ushered in the golden age of bunkers. Several European governments considered it their responsibility to provide safe hiding places for their citizens. No nation took this more seriously than Switzerland. In the nineteen-sixties, the country mandated the construction of shelter space for every inhabitant; today there are roughly nine million bunker spots for a population of 8.8 million—enough for some refugees to bring a plus-one.

In this country, the powers that be took a different approach—one made explicit in the subtitle of Garrett Graff’s 2017 book, “Raven Rock: The Story of the U.S. Government’s Secret Plan to Save Itself—While the Rest of Us Die.” Although President Eisenhower opposed a federally financed shelter program, worried that it could lead to a too-powerful military-industrial complex, President Kennedy implemented a program by which basements in churches and schools were turned into fallout shelters, marked with those signs that resemble yellow-and-black pizza slices.

Meanwhile, even if you ended up blown to smithereens, your leaders would be thriving in undercover fortresses. A number of these facilities remain, including one in Culpeper, Virginia, that was meant to house hundreds of Federal Reserve employees. Probably the most ambitious government bunker was code-named Project Greek Island, a shelter seven hundred and twenty feet beneath the Greenbrier resort, in West Virginia. Built clandestinely in the late fifties, it was intended to house the entire U.S. Congress. After passing through a twenty-five-ton blast door that blends in with the Greenbrier’s garden-club décor, our elected officials could safely be squirrelled away à la Dr. Strangelove. The facility had a cafeteria that could serve four hundred, a television studio, and a trash incinerator that could do double duty as a crematorium. It is now open to the public for tours.

From my hotel in Langdon, North Dakota, a small town seventeen miles from the Canadian border which holds the U.S. record outside Alaska for the longest stretch of below-zero weather, it’s an easy fifteen-minute drive to Anna and Jim Cleveland’s nuclear-bomb-resistant compound. I would soon learn that it’s an easy drive from anywhere to anywhere in North Dakota; as the Avis car-rental guy at the Grand Forks airport told me, “There are no turns in North Dakota.” You know you’ve arrived at the Clevelands’ place when you see two Stonehenge-y monoliths of concrete rising from the earth. One is an exhaust stack for the generators that used to be buried below; the other is a fresh-air intake. Clustered nearby are twelve shallow fibreglass domes that look like a conference of igloos designed by Louis Kahn. Each dome caps a thirty-five-foot-deep silo that formerly housed a short-range missile.

Anna and Jim Cleveland, fifty and sixty-three, welcomed me to their maximum-security home. Because of cost considerations and shifts in strategy, Congress voted to decommission their missile base, along with the four other sites that made up the Stanley R. Mickelsen Safeguard Complex, in October of 1975, one day after the facilities became fully operational.

We entered the houseplant-filled hallway of what was once the aboveground guard shack. In this building, a twenty-four-hundred-square-foot one-story structure made of beige poured concrete with a flat roof and a row of windows, security personnel would vet visitors before opening the gate that allowed entry onto the premises. For the last nine years, the guard shack has been home to Anna and Jim, plus various permutations of their thirteen children and two cats.

“We had a good-sized home in Nebraska, but when we had family get-togethers it was too small,” Jim said.

“And taxes were killing us,” Anna added.

Jim: “It’s not that we were necessarily looking for a bunker, but when you have a structure that’s underground, you don’t get taxed on the underground.” (Fact check: The taxation of underground shelters is largely determined by the state or municipality.)

They nabbed the property, which had been derelict for forty years, for next to nothing in a General Services Administration auction. But turning their bargain-basement fixer-upper into living quarters was daunting, and more expensive than they’d anticipated. They hadn’t planned on cramming the whole family into the guard shack. Anna said, “So what we envisioned when we bought the place just didn’t work.”

Their dream gone askew, the Clevelands put their missile base on the market only a year after they purchased it. In the ten years since then, fewer than five potential buyers have gone to see it. Hundreds have phoned or written about the listing, however, detailing such fantasies as turning the property into a survival community, a munitions plant, a cryptocurrency data center, or a mausoleum for cremated remains. Most inquiries, the Clevelands said, are fear-driven. “Everybody’s got a theory,” Anna said, “and everybody is just freaking out about something.”

Jim chimed in, “We even had somebody that kept talking about zombies.” Care to place a bid?

Before closing the deal, let’s walk the hundred or so yards from the guard shack to the bunker itself and take a quick tour of the underscape. The entrance is through a structure that could be a brutalist one-car garage dug into a hillock. Nearby, something that looks like a maquette of a Richard Serra sculpture is a gun-discharge station, a rusty cannister once used by G.I.s to insure that their guns were bullet-free before bringing them indoors. (It could make a serviceable umbrella stand.) After you pass through the exterior doors, you traverse a seventy-five-foot concrete tunnel, lit by strings of Christmas lights. (“Cheery,” Jim said.) At the end of the tunnel is a blast door, a behemoth weighing several tons. Twenty feet later is a second blast door, which opens onto a hundred-and-forty-five-foot hallway.

Inside, it’s so quiet that you can hear a nuclear bomb not drop. The Clevelands walked me through a warren of interconnected chambers. First we visited what they call the Tentacle Room—a gray space that had clusters of flexible electrical conduit dangling from the ceiling like rigatoni. Next was the Suspended Room, where, back in the day, missile-firing computers sat on a metal platform that was suspended from the ceiling by giant Wonka-esque springs so as to minimize any shaking caused by a nuclear detonation in the vicinity. Other cavernous rooms contained industrial fans, metal lockers, and a movie-theatre-size popcorn-maker.

When the Clevelands’ kids were young and the guard shack felt cramped, they used to go down into the bunker to play video games and do homework. Jim and Anna now use a section of the windowless lair as a studio; they have a business making mail-order kits for model-railroad enthusiasts. It can get chilly twenty-four feet below the earth’s surface, so the Clevelands initially heated the space with coal. This proved unwieldy. I saw, scattered around, the boiler they installed for the coal, the forklift they used to unload it, and the long lineup of metal bins in which it was stored. “That was silly, but we do silly things,” Jim said. Today, they wear layers of sweaters and use space heaters when they work.

The studio itself had a Santa’s-workshop vibe. The boxes lining the shelves were brimming with adorable miniature versions of the world above, intended to accessorize toy-train environments (the labels read, for instance, “Beanery Diner,” “Pete’s Tavern,” “Barrel and Box Company”). There’s room to accommodate thirty or more elves, but before reporting to work after a nuclear attack, they’d have to deposit their radiation-contaminated pointy shoes in the closet marked “FOOT GEAR DROP.”

Most of the people who visit or call about the bunker are “driven by panic stuff,” Jim said. “But we are putting a positive spin on the marketing. This is a great community in a beautiful place to live. If the end of the world happens, you’re in a good spot, too. But guess what? The sun’s going to come up tomorrow, and my taxes are still due.”

If vintage charm isn’t your thing, you might consider a hot-off-the-factory-floor bunker from Atlas Survival Shelters, prefab or custom-made to your whims and worries. “I sell on average a bunker a day,” Ron Hubbard, the founder of the company, told me over the phone from his headquarters, in Sulphur Springs, Texas. “Sales have been quite steady since COVID started, in 2020, and it hasn’t slowed down. The war in Ukraine was a big influence, and the war in Israel gave us a tiny spike,” he added.

Hubbard said that his customers are typically married, about fifty-five. Sixty per cent are male, ninety-nine per cent are conservative Christians. “At this time, Democrats are not buying bunkers,” he said. “I don’t understand it, but I guess they think everything’s fine.” Most Atlas shelters cost between a hundred thousand and five hundred thousand dollars, but they can go as low as twenty thousand and as high as several million. At the most affordable end is a precast-concrete number that Hubbard calls “a true working man’s off-the-shelf.” It comes with four cot-like bunks inside what looks like a giant bowler hat, but one with a watertight aluminum hatch and a polypropylene ladder.

I asked Hubbard if he’d seen the rendering that recently circulated of a bunker planned for a mogul in the U.S. which has a thirty-foot-deep moat that can set itself on fire in the event of an assault. He hadn’t, but he said that he’d worked with such high-net-worth individuals as the Tate brothers of Romania and the YouTuber known as MrBeast—he even lent a bunker for the Kardashians to try on their reality show. “Your normal non-eccentric billionaire is not wasteful with his money,” he told me. “They might put in a few bunkers, but they don’t want to spend more than a million for each. They might want a game room, but they don’t get too crazy.”

Hubbard has his own bunker, of course—a twelve-year-old fifty-footer equipped with a Swiss air system, gas-tight doors, and a mudroom. In December of 2012, he stayed inside it for eleven days, coinciding with the time frame that many people (reading the Mayan calendar erroneously) predicted would see the end of the world. Did he feel sheepish about that? “Look, I make bunkers,” he said. “I’m not crazy. But if the world did end, at least I was in my bunker.”

Bring your architect and your imagination—and maybe a flashlight—and, oh, while you’re at it, perhaps a pail to catch the water dripping from the stalactites. But first let yourself onto the property—ninety acres of deciduous woods in Arkansas with a trailer home and two large unfinished structures made from upcycled materials like tires. Locate the fence with the handwritten corrugated-metal sign that reads “WE BITE GO AWAY,” a nice complement to the one at the cave entrance that says “TRESPASSERS WILL BE SHOT. SURVIVORS WILL BE SHOT AGAIN.” The two signs were posted by the previous owner, a semi-recluse named John Nelson (in the event that his food stockpiles ran out, he planned to eat squirrels). Nelson, who died in 2022, willed the cave and its environs to three friends.

Two of those friends agreed to show me around the place: John Perry, a potter who looks like a folksinger and describes himself as a Bernie guy, and Tom Crum, a retired FEMA employee who, with his painter’s-brush mustache and a pair of overalls, called to mind the host of a children’s TV show. Marketing the cave as a bunker was the idea of the third friend, Rob Repin, a gold miner who lives in Washington State. Noting the high number of anxious rich people around these days, Rob wrote in an e-mail to me, “advertising as an underground shelter seems like the most bang for the buck.” In 2015, he’d bought part of a railroad tunnel in Oregon and flipped it for a hefty profit.

As Perry and Crum led me into the cave’s front room, where Nelson slept and ate, I was reminded of those old Lower East Side apartments that had the bathtub in the kitchen: Nelson had set up a shower and a faucet by connecting pipes to a rain barrel. He’d installed electricity, but the lights weren’t working the day I visited. Next stop was the vaunted worm room, reached by tiptoeing over the dirt floor. It was here, in an open space bigger than three pickleball courts, with a ceiling height of fifteen to twenty feet, that Nelson’s tens of thousands of earthworms lived, in plastic kiddie pools.

“Tell her about the time the worms—” Crum said to Perry.

“Well,” Perry interrupted, “one time, the power had gone out, and John heard this sound through the whole cave.” Perry made a slurping noise. “The earthworms were crawling all over the walls. And glistening. That’s why he kept the lights on all the time.” Evidently, if you’re a worm, lights-out means “Paaar-ty!”

Using our phone flashlights, we stumbled through a narrow passageway, through stacks of Styrofoam cups that Nelson had packed the worms in before shipping them to his worm customers. “The cave goes on for miles. I wish we had more lights, so you could see how beautiful it is,” Perry said. “Lights-out” had become a trigger phrase for me, but luckily we called it quits and made our way back to sunshine.

Later, musing about other uses for the vast worm room, I envisioned an ideal home theatre for staging a Plato-inspired shadow play or an immersive “Flintstones” remake. Or, with a cute sectional sofa, soft lighting, and a cozy area rug, you could turn this man cave into a woman cave. A skylight might be nice, too.

The next night, arriving home from my bunker-shopping trip, tired and jittery, I opened my apartment door and heard a sustained, ear-shattering beeping. My heart began to pound. Was this it? The end?! Nope. My smoke detector needed a new battery. My doomsayer friends weren’t right. Yet. ♦